This post provides a brief overview of a paper where we developed methods for measuring and testing moral dumbfounding (McHugh et al. 2017).

What is Moral Dumbfounding

Moral dumbfounding occurs when people stubbornly maintain a moral judgement, even though they can provide no reason to support their judgements (Haidt 2001; Haidt, Björklund, and Murphy 2000; Prinz 2005). Dumbfounded responses may include: (a) an admission of not having a reason for a judgement, (b) the use of an unsupported declarations (“It’s just wrong!”) to defend a judgement.

Evidence for Moral Dumbfounding

Empirical evidence for dumbfounding limited to a single study with a total sample of N = 30 (Haidt, Björklund, and Murphy 2000). Haidt, Björklund, and Murphy (2000) is widely discussed but it has not been published in peer reviewed form, and has not been directly replicated. In recent years, the existence of moral dumbfounding has been contested by some authors (e.g., Gray, Schein, and Ward 2014; Jacobson 2012; Royzman, Kim, and Leeman 2015; Sneddon 2007; Wielenberg 2014; Guglielmo 2018; Stanley, Yin, and Sinnott-Armstrong 2019)

Defining and Measuring Moral Dumbfounding

In addition to the limited evidence for moral dumbfounding, it is also apparent that there is no single agreed definition of moral dumbfounding. It was originally defined as “the stubborn and puzzled maintenance of a judgment without supporting reasons” (Haidt, Björklund, and Murphy 2000, 2; see also, Haidt and Hersh 2001, 194; Haidt and Björklund 2008, 197) but the use of this full definition varies. From surveying the literature we identified the “maintenance of a judgement in the absence of supporting reasons” as essential elements of dumbfounding.

Using this definition we proposed two possible measurable indicators of moral dumbfounding. Firstly, participants may become aware that they do not have reasons and acknowledge this (admissions of not having reasons). Secondly, participants may fail to provide reasons. The use of unsupported declarations or tautological reasons as justifications for a judgement may be viewed as evidence of a a failure to provide reasons. Stating “it’s just wrong” or “because it’s wrong” does not answer the question “do you have a reason for your judgement?” (Mallon and Nichols 2011, 285).

Our Studies

Due to the weak evidence for moral dumbfounding we set out to investigate if the phenomenon is real, and if it can be measured.

We conducted 3 studies:

- Study 1: Interview - replication of Haidt, Björklund, and Murphy (2000)

- Study 2: Computer task 1

- Study 3: Computer task 2 (college sample: 3a; MTurk Sample: 3b)

Study 1 (Interview)

Study 1 was a video recorded interview.

31 participants (MIC/UL students and alumni) (15 female, 16 male, 0 other; Mage = 28.83, min = 19, max = 64, SD = 10.99) took part.

- Participants presented with 4 scenarios and asked to judge the behaviour of the characters in the scenarios (Heinz, Cannibal, Incest, Trolley see end of this post for full text)

- The Experimenter challenged the judgement

- Videos were coded for key responses of interest:

- Admissions of not having reasons

- Unsupported declarations

Results

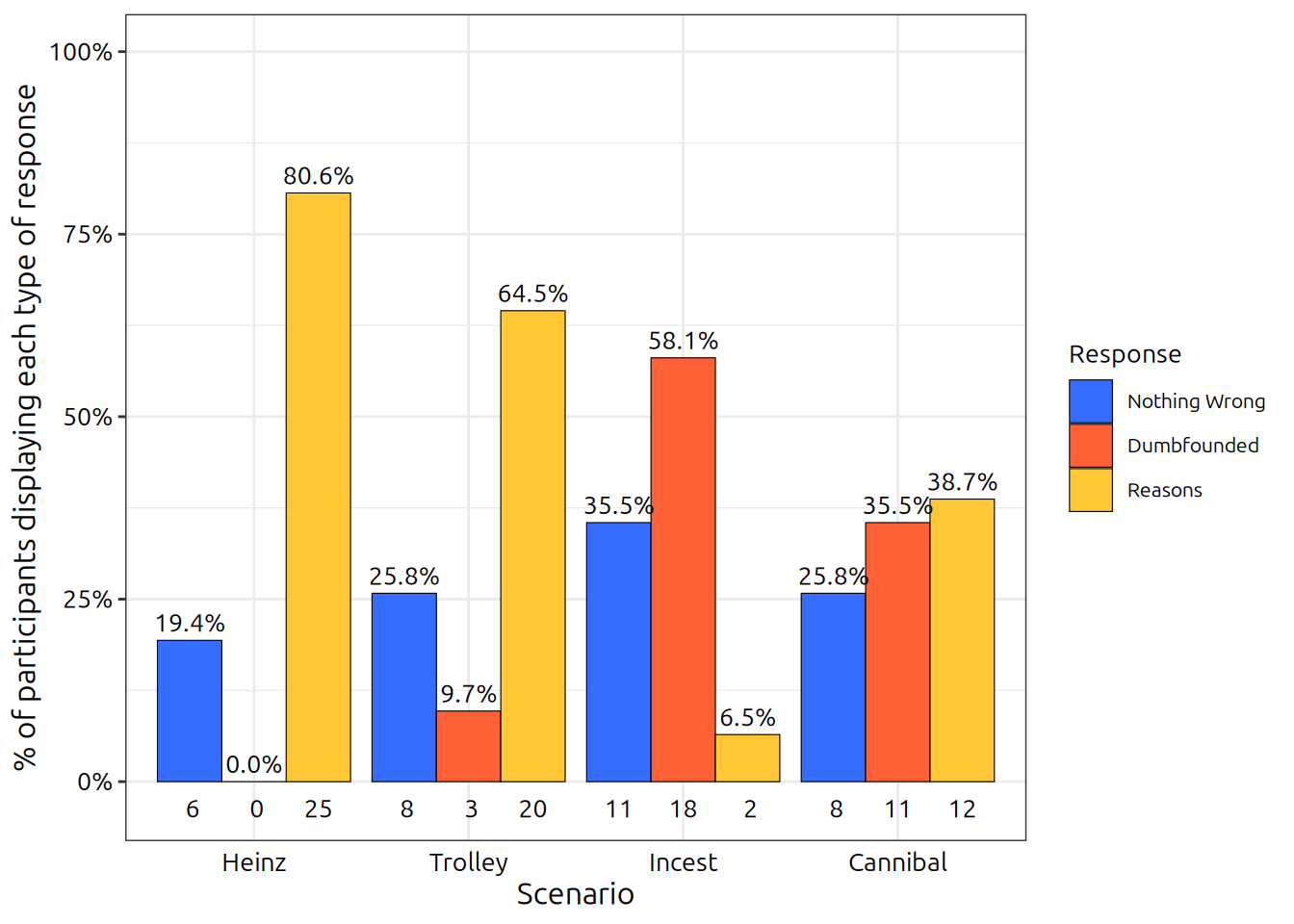

Twenty two of the 31 participants (70.97%) produced a dumbfounded response at least once. (admissions of not having reasons; or the use of an unsupported declaration as a justification)

- Examples of such responses included:

- “It just seems wrong and I cannot explain why, I don’t know”

- “because I just think it’s wrong, oh God, I don’t know why, it’s just [pause] wrong”.

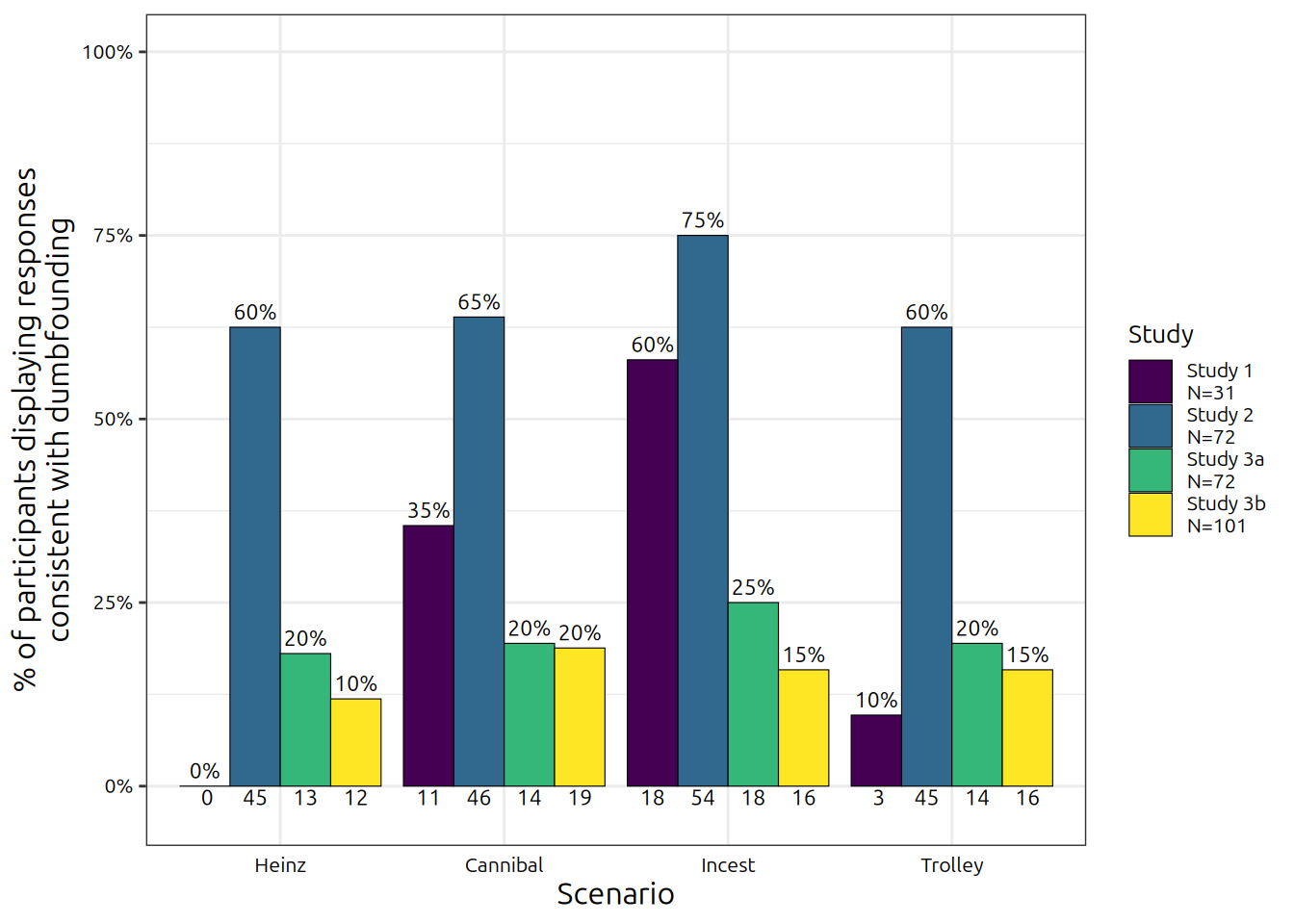

The rates of each type of response for each Scenario are displayed in Figure @ref(fig:figdumb1Interview)

Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.

Warning: Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Warning: The dot-dot notation (`..count..`) was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

ℹ Please use `after_stat(count)` instead.

Behavioural Responses

In addition to coding the videos for dumbfounded responding, we investigated a range of verbal and non-verbal behavioural responses. We found significant differences between dumbfounded participants and non-dumbfounded participants across a small number of variables. There were significant differences in time spent

- Laughing

- Smiling

- in Silence

(with higher rates of each in dumbfounded participants)

We found no differences in

- verbal hesitations; non-verbal hesitations

- changing posture; fidgeting/hands on the self

- frowning

Importantly, there were no differences depending on which measure of dumbfounding was used

(Admissions of not having reasons / Unsupported declarations)

Study 2 (Computer Task)

The aim of Study 2 was to address limitations of Study 1. Study 1 suffered from a very low N. Interviews require a lot of time/resources. In Study 2 we attempted to develop standardised materials to study moral dumbfounding on a larger scale.

72 participants (MIC/UL students and alumni; 52 female, 20 male, 0 other; Mage = 21.18, min = 18, max = 50, SD = 5.18) took part.

- Computer based task: Same scenarios (Heinz, Cannibal, Incest, Trolley)

- Series of counter-arguments challenged judgements

- Dumbfounding measured using Critical Slide

- The critical slide contained a statement defending the behaviour and a question as to how the behaviour could be wrong

Sample Critical Slide

“Julie and Mark’s actions did not harm anyone or negatively affect anyone. How can there be anything wrong with what they did?”

- There is nothing wrong

- Incest is just wrong

- It’s wrong and I can provide a valid reason

(The selecting of option 2, the unsupported declaration, was taken to be a dumbfounded response)

Results

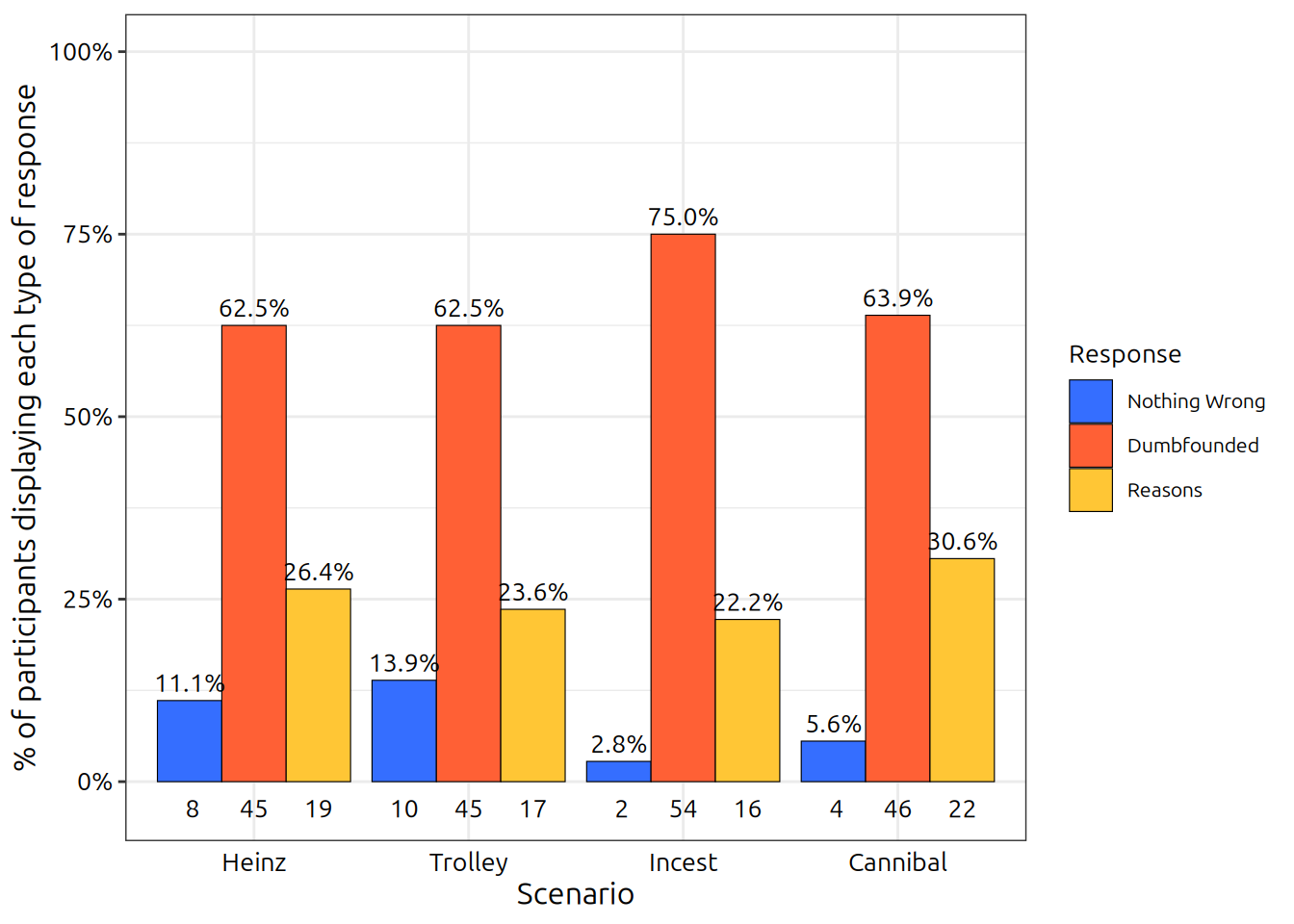

Extremely high rates of dumbfounded responding were recorded, see Figure @ref(fig:figdumb1comp1).

Warning: Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Study 3 (Revised Computer Task)

The aim of Study 3 was to address limitations in Study 2. Extremely high rates of observed dumbfounded responding not representative of the phenomenon. We hypothesised that selecting an unsupported declaration was a lazy response.

173 participants

(99 female, 73 male, 1 other; Mage = 30.53, min = 18, max = 69, SD = 12.27)

MIC/UL students and alumni, N = 72

(46 female, 26 male, 0 other; Mage = 21.8, min = 18, max = 46, SD = 3.91)

MTurk N = 101

(53 female, 47 male, 1 other; Mage = 36.58, min = 18, max = 69, SD = 12.45)

- Same procedure as Study 2 with:

- Change to Critical Slide

- Explicit admissions replaced Unsupported Declarations

- ‘Open-ended response’ option after Critical Slide

- Responses coded for Unsupported Declarations

Sample Critical Slide

“Julie and Mark’s actions did not harm anyone or negatively affect anyone. How can there be anything wrong with what they did?”

- There is nothing wrong

- It’s wrong but I can’t think of a reason

- It’s wrong and I can provide a valid reason

(Again, the selecting of option 2, this time the admission of not having a reason, was taken to be a dumbfounded response)

Results - Admissions Only

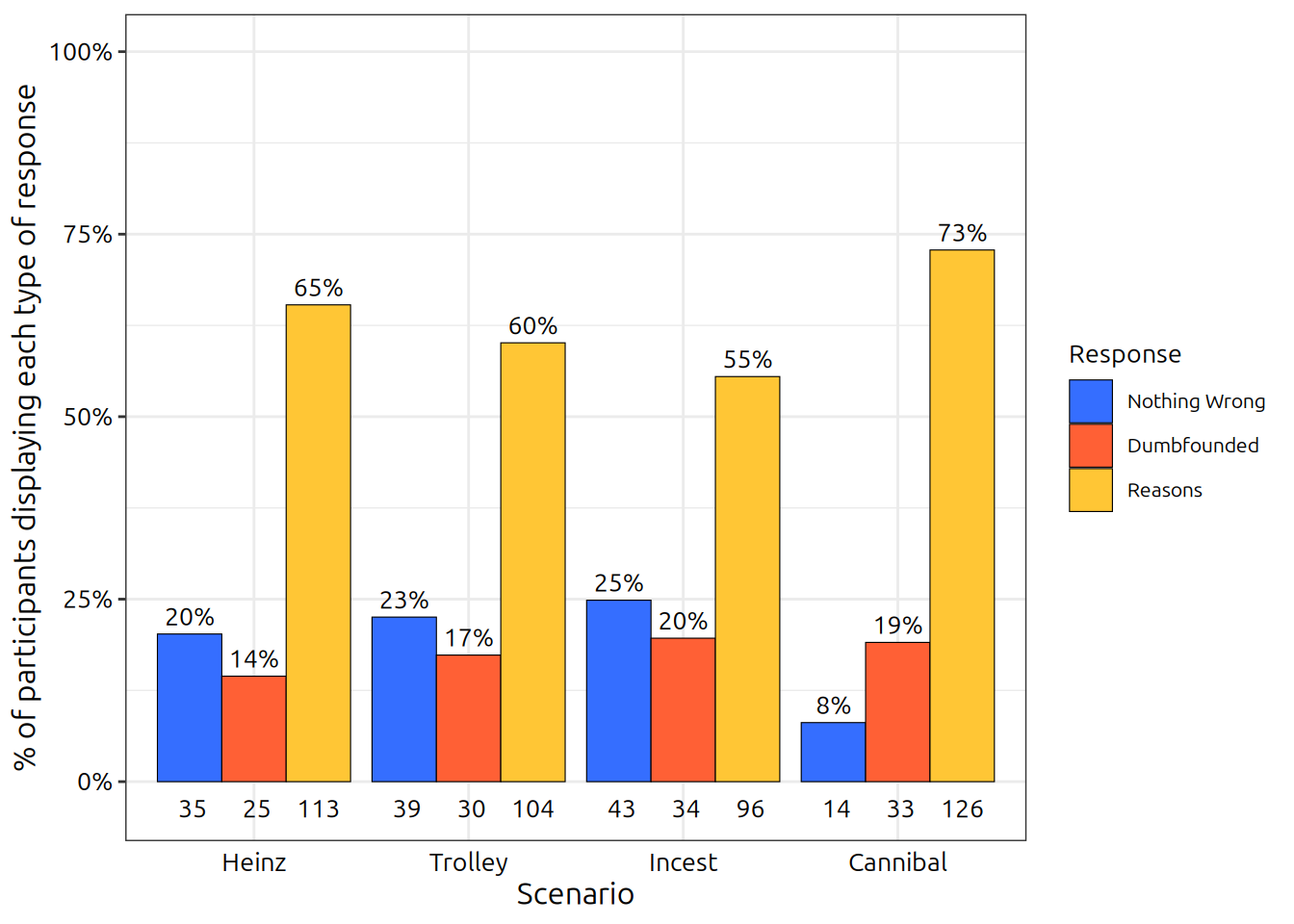

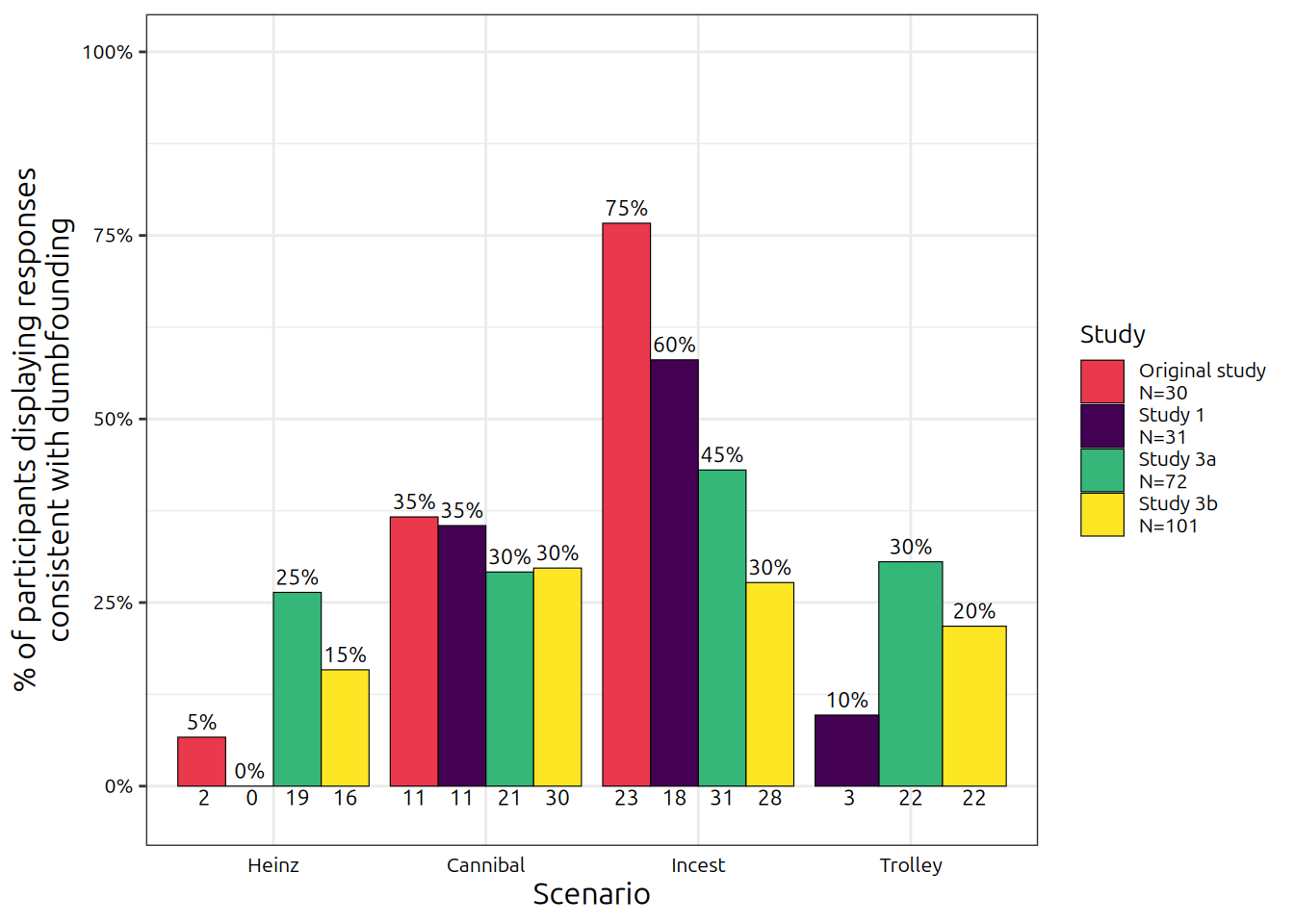

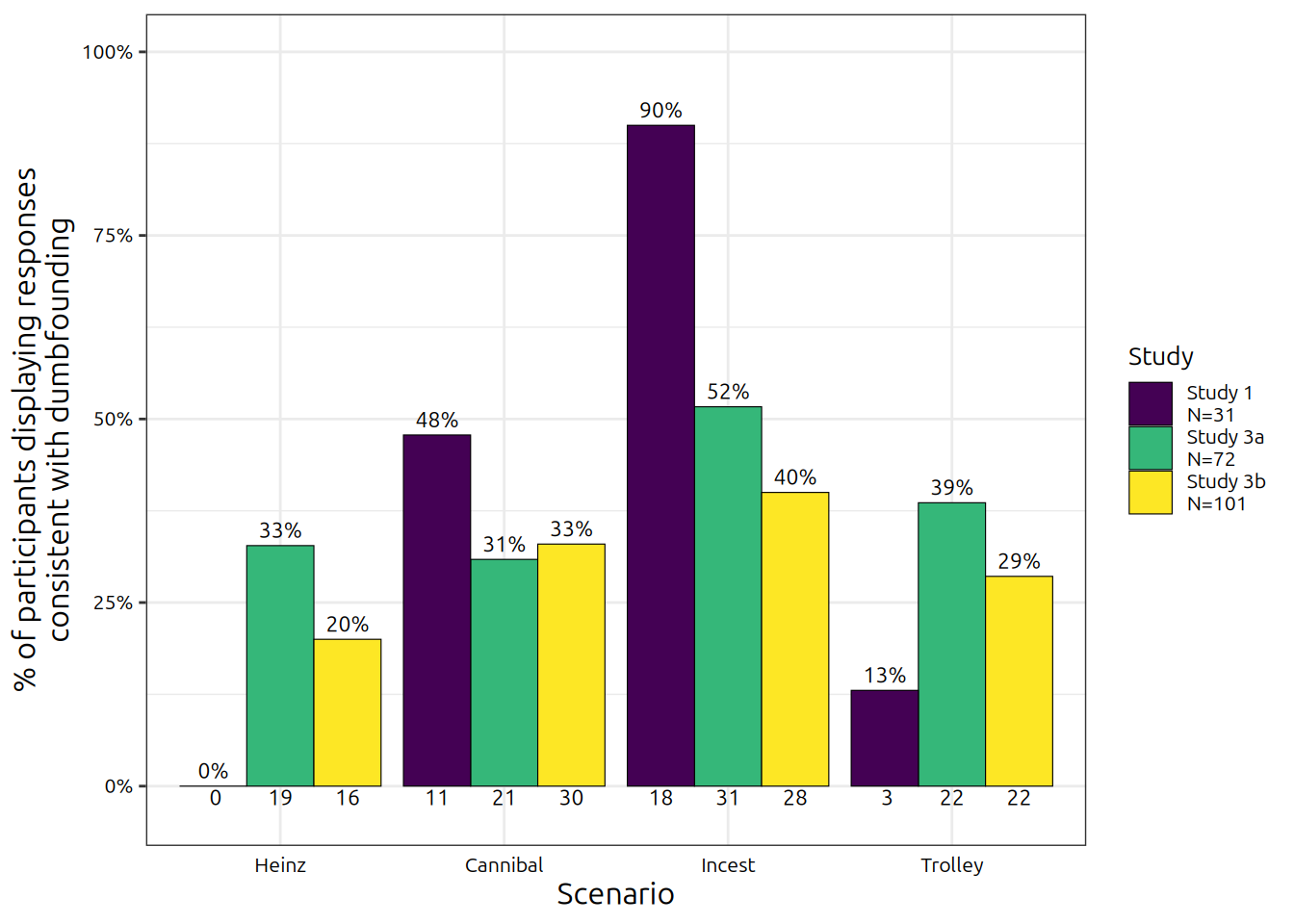

We have provided two sets of results below, firstly the results with just the responses to the critical slide. Following this we include the open-ended responses coded for unsupported declarations. Figure @ref(fig:figdumb1comp2) shows the rate of each response to the critical slide for each scenario.

Warning: Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

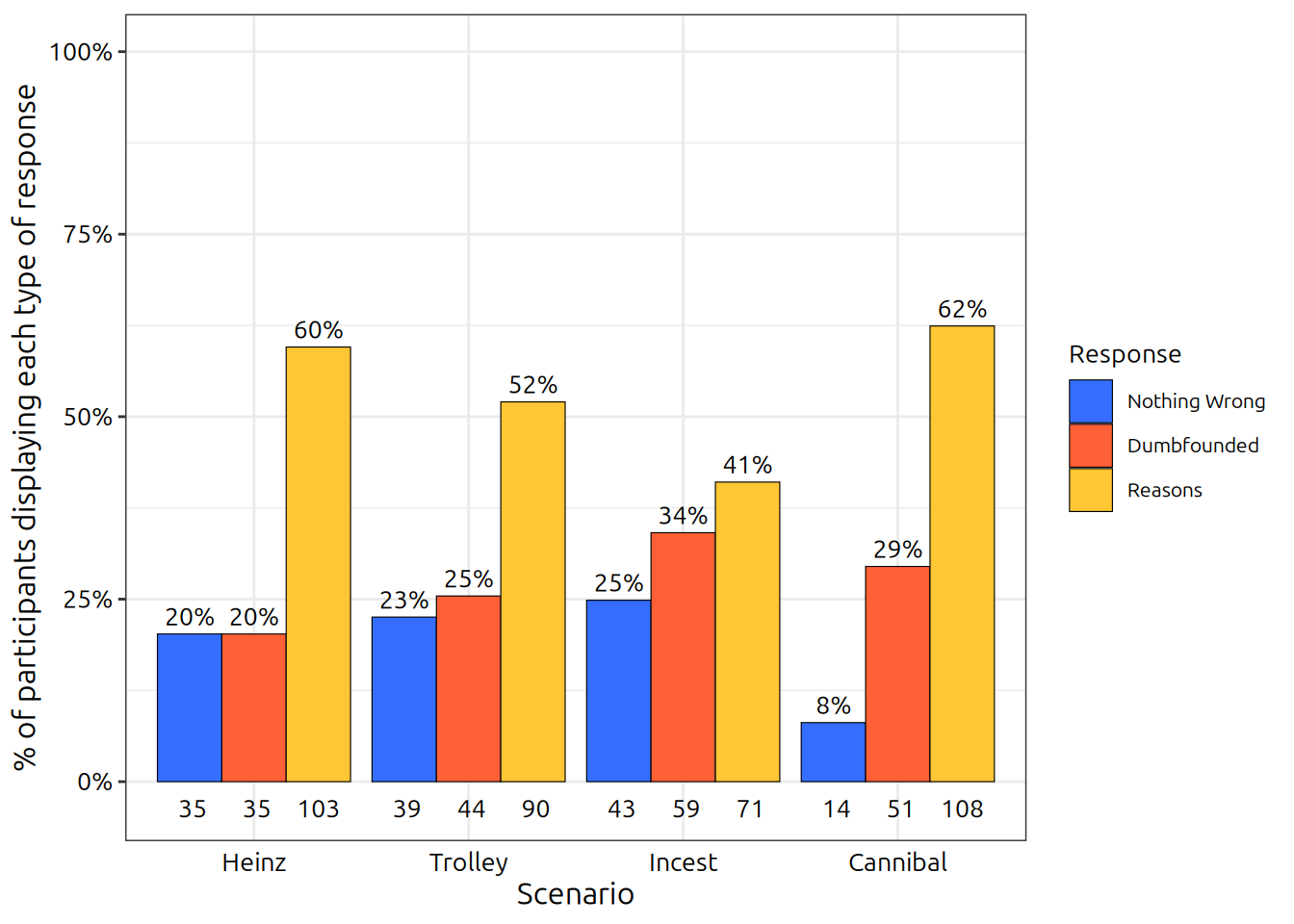

Results - including open-ended responses

Figure @ref(fig:figdumb1comp2string) shows the rates of each type of response, when the coded open-ended responses are included.

Warning: Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Use of `test$perc` is discouraged.

ℹ Use `perc` instead.

Discussion

The goal of this research was to examine the replicability of dumbfounded responding following a moral judgement task, and identify specific measurable responses that may be viewed as indicators of moral dumbfounding. Three studies, with a combined total sample of N = 276, were conducted in an attempt to replicate and extend the original demonstration (N = 30) of moral dumbfounding by Haidt, Björklund, and Murphy (2000). We predicted that dumbfounded responses would be evoked when participants were required to provide justification for their moral judgements, when their basic intuitive justifications had been refuted. Two measures of moral dumbfounding were taken, an explicit acknowledgement of the absence of reasons, and a failure to provide reasons when pushed. Rates of observed dumbfounding vary depending on which measure is being employed.

Conclusion

Moral dumbfounding can be reliably elicited using standardised methods. Rates of dumbfounded responding are generally low, with the majority of participants providing reasons for their judgements. Future research is required to establish why this occurs.

Additional Material

Moral Scenarios

Heinz

In Europe, a woman was near death from a very bad disease, a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium for which a druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to make. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying, and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said, “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So, Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. The druggist had Heinz arrested and charged.

Trolley

A Trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. It will kill them all on impact. Paul is on a bridge under which it will pass. He can stop it by putting something very heavy in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to him – Paul’s only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Paul decides to push the man.

Cannibal

Jennifer works in a medical school pathology lab as a research assistant. The lab prepares human cadavers that are used to teach medical students about anatomy. The cadavers come from people who had donated their body for the general use of the researchers in the lab. The bodies are normally cremated, however, severed cuts may be disposed of at the discretion of lab researchers, One night Jennifer is leaving the lab when she sees a body that is going to be discarded the next day. Jennifer was a vegetarian, for moral reasons. She thought it was wrong to kill animals for food. But then, when she saw a body about to be cremated, she thought it was irrational to waste perfectly edible meat. So she cut off a piece of flesh, and took it home and cooked it. The person had died recently of a heart attack, and she cooked the meat thoroughly, so there was no risk of disease.

Incest

Julie and Mark, who are brother and sister, are travelling together in France. They are both on summer vacation from college. One night they are staying alone in a cabin near the beach. They decide that it would be interesting and fun if they tried making love. At very least it would be a new experience for each of them. Julie was already taking birth control pills, but Mark uses a condom too, just to be safe. They both enjoy it, but they decide not to do it again. They keep that night as a special secret between them, which makes them feel even closer to each other.

Combined Tables

(#tab:tab1judge) Ratings of each scenario for each study

| Study 1 |

Initial: Wrong |

27 |

87.1% |

25 |

80.65% |

26 |

83.87% |

23 |

74.19% |

|

Initial: Neutral |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

|

Initial: OK |

4 |

12.9% |

6 |

19.35% |

5 |

16.13% |

8 |

25.81% |

|

Revised: Wrong |

26 |

83.87% |

23 |

74.19% |

20 |

64.52% |

22 |

70.97% |

|

Revised: Neutral |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

1 |

3.23% |

|

Reviesd: OK |

5 |

16.13% |

8 |

25.81% |

11 |

35.48% |

8 |

25.81% |

| Study 2 |

Initial: Wrong |

53 |

73.61% |

68 |

94.44% |

63 |

87.5% |

50 |

69.44% |

|

Initial: Neutral |

9 |

12.5% |

3 |

4.17% |

3 |

4.17% |

6 |

8.33% |

|

Initial: OK |

10 |

13.89% |

1 |

1.39% |

6 |

8.33% |

16 |

22.22% |

|

Revised: Wrong |

51 |

70.83% |

67 |

93.06% |

66 |

91.67% |

48 |

66.67% |

|

Revised: Neutral |

7 |

9.72% |

3 |

4.17% |

3 |

4.17% |

9 |

12.5% |

|

Reviesd: OK |

14 |

19.44% |

2 |

2.78% |

3 |

4.17% |

15 |

20.83% |

| Study 3a |

Initial: Wrong |

54 |

75% |

67 |

93.06% |

61 |

84.72% |

48 |

66.67% |

|

Initial: Neutral |

6 |

8.33% |

3 |

4.17% |

7 |

9.72% |

10 |

13.89% |

|

Initial: OK |

12 |

16.67% |

2 |

2.78% |

4 |

5.56% |

14 |

19.44% |

|

Revised: Wrong |

53 |

73.61% |

67 |

93.06% |

57 |

79.17% |

43 |

59.72% |

|

Revised: Neutral |

11 |

15.28% |

4 |

5.56% |

12 |

16.67% |

15 |

20.83% |

|

Reviesd: OK |

8 |

11.11% |

1 |

1.39% |

3 |

4.17% |

14 |

19.44% |

| Study 3b |

Initial: Wrong |

81 |

80.2% |

85 |

84.16% |

71 |

70.3% |

66 |

65.35% |

|

Initial: Neutral |

9 |

8.91% |

13 |

12.87% |

20 |

19.8% |

14 |

13.86% |

|

Initial: OK |

11 |

10.89% |

3 |

2.97% |

10 |

9.9% |

21 |

20.79% |

|

Revised: Wrong |

87 |

86.14% |

82 |

81.19% |

73 |

72.28% |

59 |

58.42% |

|

Revised: Neutral |

10 |

9.9% |

15 |

14.85% |

19 |

18.81% |

17 |

16.83% |

|

Reviesd: OK |

4 |

3.96% |

4 |

3.96% |

9 |

8.91% |

25 |

24.75% |

(#tab:tab2dumb) Observed frequency and percentage of each of the responses: dumbfounded, nothing wrong, and reasons provided

| Study 1 |

Nothing wrong |

6 |

19.35% |

8 |

25.81% |

11 |

35.48% |

8 |

25.81% |

|

Dumbfounded |

0 |

0% |

11 |

35.48% |

18 |

58.06% |

3 |

9.68% |

|

(admissions) |

0 |

0% |

8 |

25.81% |

10 |

32.26% |

3 |

9.68% |

|

(declarations) |

0 |

0% |

3 |

9.68% |

8 |

25.81% |

0 |

0% |

|

Reasons |

25 |

80.65% |

12 |

38.71% |

2 |

6.45% |

20 |

64.52% |

| Study 2 |

Nothing wrong |

8 |

11.11% |

4 |

5.56% |

2 |

2.78% |

10 |

13.89% |

|

Dumbfounded |

45 |

62.5% |

46 |

63.89% |

54 |

75% |

45 |

62.5% |

|

Reasons |

19 |

26.39% |

22 |

30.56% |

16 |

22.22% |

17 |

23.61% |

| Study 3a |

Nothing wrong |

14 |

19.44% |

4 |

5.56% |

12 |

16.67% |

15 |

20.83% |

| (critical slide) |

Dumbfounded |

13 |

18.06% |

14 |

19.44% |

18 |

25% |

14 |

19.44% |

|

Reasons |

45 |

62.5% |

54 |

75% |

42 |

58.33% |

43 |

59.72% |

| Study 3a |

Nothing wrong |

14 |

19.44% |

4 |

5.56% |

12 |

16.67% |

15 |

20.83% |

| (coded) |

Dumbfounded |

19 |

26.39% |

21 |

29.17% |

31 |

43.06% |

22 |

30.56% |

|

Reasons |

39 |

54.17% |

47 |

65.28% |

29 |

40.28% |

35 |

48.61% |

| Study 3b |

Nothing wrong |

21 |

20.79% |

10 |

9.9% |

31 |

30.69% |

24 |

23.76% |

| (critical slide) |

Dumbfounded |

12 |

11.88% |

19 |

18.81% |

16 |

15.84% |

16 |

15.84% |

|

Reasons |

68 |

67.33% |

72 |

71.29% |

54 |

53.47% |

61 |

60.4% |

| Study 3b |

Nothing wrong |

21 |

20.79% |

10 |

9.9% |

31 |

30.69% |

24 |

23.76% |

| (coded) |

Dumbfounded |

16 |

15.84% |

30 |

29.7% |

28 |

27.72% |

22 |

21.78% |

|

Reasons |

64 |

63.37% |

61 |

60.4% |

42 |

41.58% |

55 |

54.46% |

(#tab:tab3Qs) Responses to post-discussion questionnaire questions

| Study 1 |

Changed mind |

2.87 |

3.40 |

2.63 |

2.60 |

|

Confidence |

5.30 |

4.77 |

5.40 |

5.07 |

|

Confused |

3.00 |

3.67 |

3.33 |

3.70 |

|

Irritated |

3.00 |

3.33 |

3.13 |

3.37 |

|

‘Gut’ |

5.23 |

5.20 |

4.97 |

5.07 |

|

‘Reason’ |

4.83 |

4.40 |

4.43 |

4.77 |

|

Gut minus Reason |

0.40 |

0.80 |

0.53 |

0.30 |

| Study 2 |

Confidence |

6.10 |

5.86 |

5.62 |

5.26 |

|

Confused |

2.40 |

3.08 |

4.14 |

3.17 |

|

Irritated |

4.58 |

4.68 |

4.32 |

4.28 |

|

‘Gut’ |

5.29 |

5.54 |

5.82 |

4.96 |

|

‘Reason’ |

4.89 |

5.19 |

4.89 |

4.93 |

|

Gut minus Reason |

0.40 |

0.35 |

0.93 |

0.03 |

| Study 3a |

Changed mind |

2.38 |

1.67 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

|

Confidence |

5.22 |

5.50 |

5.38 |

4.81 |

|

Confused |

2.75 |

2.96 |

3.25 |

2.89 |

|

Irritated |

3.94 |

4.64 |

4.07 |

3.60 |

|

‘Gut’ |

4.78 |

5.44 |

5.44 |

4.92 |

|

‘Reason’ |

5.07 |

5.26 |

5.11 |

5.06 |

|

Gut minus Reason |

-0.29 |

0.18 |

0.33 |

-0.14 |

| Study 3b |

Changed mind |

1.74 |

1.60 |

1.57 |

1.83 |

|

Confidence |

5.78 |

6.16 |

5.81 |

5.36 |

|

Confused |

2.06 |

2.07 |

2.12 |

2.22 |

|

Irritated |

4.42 |

4.01 |

3.56 |

3.39 |

|

‘Gut’ |

4.42 |

4.43 |

4.47 |

4.01 |

|

‘Reason’ |

5.46 |

5.69 |

5.26 |

5.58 |

|

Gut minus Reason |

-1.04 |

-1.27 |

-0.79 |

-1.57 |

References

Crockett, Molly J. 2013.

“Models of Morality.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17 (8): 363–66.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.005.

Cushman, Fiery A. 2013.

“Action, Outcome, and Value A Dual-System Framework for Morality.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 17 (3): 273–92.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313495594.

Gray, Kurt James, Chelsea Schein, and Adrian F. Ward. 2014.

“The Myth of Harmless Wrongs in Moral Cognition: Automatic Dyadic Completion from Sin to Suffering.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 143 (4): 1600–1615.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036149.

Greene, Joshua David. 2008. “The Secret Joke of Kant’s Soul.” In Moral Psychology Volume 3: The Neurosciences of Morality: Emotion, Brain Disorders, and Development, 35–79. Cambridge (Mass.): the MIT press.

Guglielmo, Steve. 2018.

“Unfounded Dumbfounding: How Harm and Purity Undermine Evidence for Moral Dumbfounding.” Cognition 170 (January): 334–37.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.08.002.

Haidt, Jonathan. 2001.

“The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment.” Psychological Review 108 (4): 814–34.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814.

Haidt, Jonathan, and Fredrik Björklund. 2008. “Social Intuitionists Answer Six Questions about Moral Psychology.” In Moral Psychology Volume 2, The Cognitive Science of Morality: Intuition and Diversity, edited by Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, 181–217. London: MIT.

Haidt, Jonathan, Fredrik Björklund, and Scott Murphy. 2000. “Moral Dumbfounding: When Intuition Finds No Reason.” Unpublished Manuscript, University of Virginia.

Haidt, Jonathan, and Matthew A. Hersh. 2001.

“Sexual Morality: The Cultures and Emotions of Conservatives and Liberals.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 31 (1): 191–221.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02489.x.

Jacobson, Daniel. 2012. “Moral Dumbfounding and Moral Stupefaction.” In Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics, 2:289.

Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1969. Stages in the Development of Moral Thought and Action. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Mallon, Ron, and Shaun Nichols. 2011.

“Dual Processes and Moral Rules.” Emotion Review 3 (3): 284–85.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073911402376.

McHugh, Cillian, Marek McGann, Eric R. Igou, and Elaine L. Kinsella. 2017.

“Searching for Moral Dumbfounding: Identifying Measurable Indicators of Moral Dumbfounding.” Collabra: Psychology 3 (1): 1–24.

https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.79.

Prinz, Jesse J. 2005. “Passionate Thoughts: The Emotional Embodiment of Moral Concepts.” In Grounding Cognition: The Role of Perception and Action in Memory, Language, and Thinking, edited by Diane Pecher and Rolf A. Zwaan, 93–114. Cambridge University Press.

Royzman, Edward B., Kwanwoo Kim, and Robert F. Leeman. 2015. “The Curious Tale of Julie and Mark: Unraveling the Moral Dumbfounding Effect.” Judgment and Decision Making 10 (4): 296–313.

Sneddon, Andrew. 2007.

“A Social Model of Moral Dumbfounding: Implications for Studying Moral Reasoning and Moral Judgment.” Philosophical Psychology 20 (6): 731–48.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09515080701694110.

Stanley, Matthew L, Siyuan Yin, and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong. 2019. “A Reason-Based Explanation for Moral Dumbfounding.” Judgment and Decision Making 14 (2): 10.

Topolski, Richard, J. Nicole Weaver, Zachary Martin, and Jason McCoy. 2013.

“Choosing Between the Emotional Dog and the Rational Pal: A Moral Dilemma with a Tail.” Anthrozoös 26 (2): 253–63.

https://doi.org/10.2752/175303713X13636846944321.

Wielenberg, Erik J. 2014. Robust Ethics: The Metaphysics and Epistemology of Godless Normative Realism. Oxford, United Kingdom: OUP Oxford.